Notation of an Archetype

Representations Through Counterpoint in King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band

Introduction

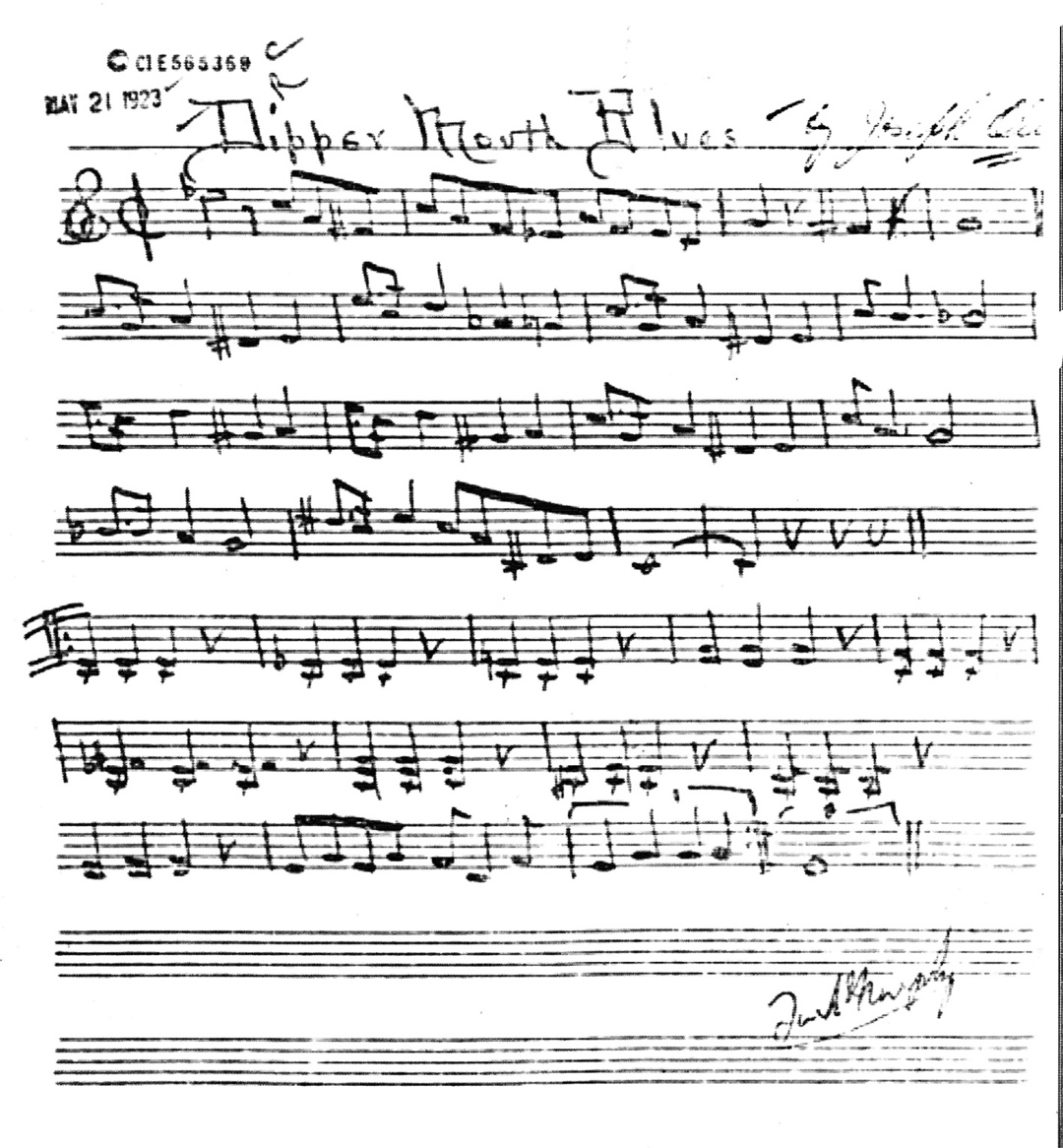

On 21 May 1923 a copyright deposit for a composition named Dipper Mouth Blues (Fig 1) 1 was registered at the Library of Congress. It is the only blues by King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band that was recorded during both of the band’s first two recording sessions in 1923. The recordings became an important document of the practice of collective improvisation in the New Orleans polyphonic style. The first recording 2 was made on 6 April 1923 for the Gennett record company in Richmond, Indiana. It is among the first audio recordings documenting a jazz ensemble composed of musicians of Afro-American descent. The recording contains King Oliver’s famous plunger mute solo and his duo work with Louis Armstrong, which was this ensemble’s trademark. The composition outlived the crossover to the Swing Era as Fletcher Henderson’s Sugar Foot Stomp. 3

Figure 1 Copyright deposit Dipper Mouth Blues. 4

Sadly enough, these recordings of New Orleans Jazz document the genesis of Jazz only years into its development. The record companies were owned by white people and New Orleans artists of colour were excluded from recording, resulting in insufficient audio documentation of the music before 1923. 5 In the absence of evidence on recordings, we have to rely on the testimony of contemporary witnesses like Edmond Souchon, who wrote in 1960:

I believe without fear of memory-tricks that by the time Oliver was playing at Tulane gymnasium, he had acquired a technique that was much more smooth, and that his band was adapting itself to the white dances more and more. At Big 25 it was a hard-hitting, rough and ready, full of fire and drive. He subdued this to please the different patrons at the gym dances. 6

To form a theory of this music we have to rely on the analysis of transcriptions of the recordings and the copyright deposits.

This paper is based on the author’s transcription of the recording of Dipper Mouth Blues and its copyright deposit. The close look at the connection between the copyright deposit and the recording gives us a deep insight into the thinking of musicians at the time. What surfaces is a modular counterpoint that is negotiated anew between the musicians in every performance. Since the copyright deposit can’t be categorised as a lead sheet, the term ‘notation of an archetype’ is introduced, based on the corresponding concept by C.G. Jung, enabling us to see the recordings and the copyright deposit as representations of the same archetype.

King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band

The trumpet player and bandleader King Oliver left New Orleans in 1918 and moved to Chicago where he founded King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band in 1920. 7 When the second cornet player Louis Armstrong joined the band in 1922 it was to be the starting point of an unparalleled career in Jazz. 8 This makes King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band not only an important link in the genealogy of trumpet players in Jazz, it also produced the most reliable document of the practice of New Orleans polyphonic Jazz, allowing us to grasp this style as practiced before the swing era. 9

The Copyright Deposit

In 1923 the copyright for a piece of music could only be secured by writing it down. An audio recording would not suffice. 10 The copyright deposit consisted of a copy of the sheet music that was sent to the Library of Congress. According to the stamp in the upper left corner, delivery of Dipper Mouth Blues took place on 21 May 1923.

The author of the copyright deposit is disputed. While the signature in the upper right corner of the deposit states Oliver as composer and Lil Hardin is named as arranger 11 under the name from her previous marriage Lillian Johnson, Louis Armstrong also gets credit for the tune. Thomas Brothers provides three clues supporting this claim; first, the title being his frequently used nickname, second, Bill Johnson reporting in 1938 that Armstrong was the composer, and third, the fact that Don Redman, arranger for the band Fletcher Henderson and his Orchestra, chose the tune out of Armstrong’s little manuscript book of music in New York in 1925. 12 However, Baby Dodds reports that the whole band had been involved in the process of creating the tune. He reports: “the really fine thing about the number was the way we worked it out together. There was no one individual star, but everybody had to come through”. 13

Genesis of the Recording

The first recording session of King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band took place on 5 and 6 April 1923, in Richmond, Indiana, for the Gennett record company. The track Dipper Mouth Blues was recorded on the second day. The band consisted of the bandleader and cornet player King Oliver, the cornet player Louis Armstrong, the trombone player Honoré Dutrey, the clarinet player Johnny Dodds, Bill Johnson on banjo, Lil Hardin on piano and Baby Dodds on percussion instruments. The third take of Dipper Mouth Blues with the catalogue number Ge 5132-A is the only surviving take as the first and second got destroyed, having been rejected by Gennett. 14

Recording technology at that time was primitive. The musicians were in one room, positioned around a funnel built into a wall. Behind the funnel a membrane was connected to a needle that would cut grooves into wax disk. For the wax to have the optimum consistency, room temperature had to be around 23°C. The bass and bass drum would make the needle jump and thus render the recording unusable. In the case of King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band these instruments were substituted; drummer Baby Dodds instead used woodblocks and bass player Bill Johnson switched to the banjo. The length of the recording was determined by the size of the wax disk ranging up to around three minutes. After two minutes and 30 seconds a red light would light up to tell the musicians to end the performance soon. 15

Analysis of the Copyright Deposit

The copyright deposit consists of only one written melody in treble clef; it lacks chord symbols or tab notation for an accompanying instrument. Formally, it consists of an introduction of four bars, a theme in the form of a twelve-bar blues and a two- to three-voice stop time chorus of another twelve bars. There are no instructions on how to execute the arrangement to realise the polyphony or any other accompaniment. This is also due to the fact that only melodies can be subject to copyright, not chords or chord progressions.

There are a few oddities that catch the eye of today’s reader. In the introduction, the F sharp that is the root of the arpeggio of the diminished seventh chord on F sharp is stated in the first bar, but missing in the second. In the second, fifth and sixth bar of the chorus stating the melody, the pitch E is written, although we expect an E flat, which would conform to blues harmony and correspond to the pitches heard on the recording. The stop time chorus is incomplete insofar as we expect three voices all the way through.

The copyright deposit was written with one goal in mind: to secure the copyright. The writer of the manuscript did obviously not pay a great deal of attention to pitches, resulting in sharps and flats being omitted. This leads to the conclusion that the sheet music was not intended to serve as a playing score. The true nature of the copyright deposit can only be determined by comparing it to the transcription of the recording.

Analysis of the Recording

The Form

The recording begins with an introduction that is followed by nine runs of the twelve-bar blues form.

The introduction lasts four measures and is arranged around the arpeggio of the diminished seventh chord on F sharp. This chord functions as the secondary seventh chord to the dominant of C. In the first two measures the brass instruments play alone, the clarinet joining only in the third measure. This gives the introduction the character of a fanfare.

The first two choruses state the theme in the New Orleans polyphonic style. The following clarinet solo is accompanied by stop-time for two choruses. The fifth chorus is another take on the theme, but only with Louis Armstrong on cornet; King Oliver rests to save energy for the following chorus where he is playing his solo. His solo lasts three choruses and is accompanied by the clarinet and trombone in polyphonic style, whereas Louis Armstrong supports the soloist with rhythmicised pedal notes and melodic fragments. Before the last chorus where the theme is again stated in polyphonic style we hear the famous vocal break where Bill Johnson shouts, “Let’s play that thing!” which was originally improvised to remind Baby Dodds to play on the forgotten drum break. 16 The performance closes with the repetition of the last two bars.

We can assume that this sequence was agreed upon before recording because the length of the recording was limited to three minutes, and the available time had to be planned in order to use it to the maximum. However, relics of musical signals that could be used in a more open setting such as a live performance can be found. They can be found in the bar before the start of a chorus, much as a signal for what type of chorus would follow. Before every chorus stating the theme, King Oliver plays a melodic pick-up that is then joined by Honoré Dutrey on trombone with a glissando from D sharp to E. Before the first stop time chorus King Oliver plays a repeated G as an anticipation of the following note repetitions. In the bar before the two choruses that are his own solo he is completely alone. Since we do not have recordings or verbal testimonies it suggests itself that in live performances the sequence and lengths of the sections would be handled more freely and the use of musical signals would have an immediate impact on the form.

For the purpose of investigating the connection of the copyright deposit and the transcription of the recording the analysis focuses on the first two choruses, as they are distinguishable as head choruses 1 and 2.

The Roles of the Individual Instruments

The Rhythm Section

The rhythm section consists of Bill Johnson on banjo, Lil Hardin on piano and Baby Dodds on percussion. The banjo assumes an accompanying role by playing chords on all four beats of the measure when it is not arranged to fit the introduction and the stop-time chorus. The same goes for the piano. As stated before, Baby Dodds uses woodblocks instead of the bass drum. He plays a cymbal as his entrance in the fourth measure on beat 3 and continues with quarter notes with or without swinging off-beat eight notes according to the banjo and piano part.

The Trombone

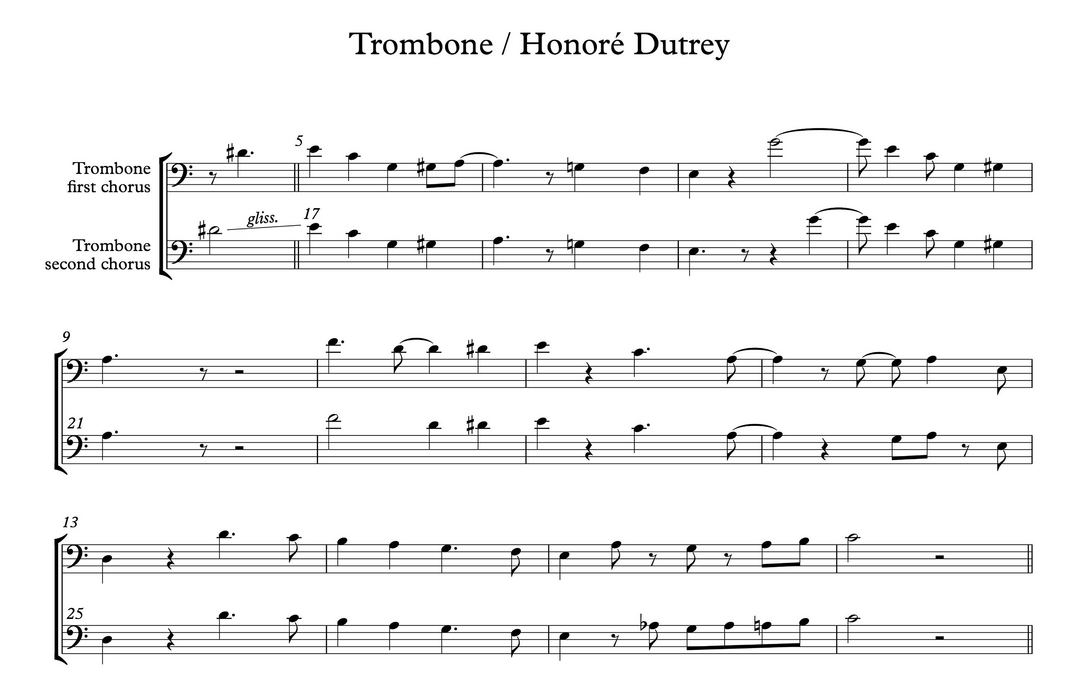

Honoré Dutrey on trombone plays the same countermelody in the first and second chorus, the only slight differences are the rhythmic anticipations in the first, third, sixth, and eighth bar of the form (see fig. 2). The second to last bar of the form has two versions: one with and one without the chromatic note A flat. With its irregular phrase lengths of 3, 2, 4, and 3 measures, the countermelody is constructed to reach across the symmetry of the three four-bar phrases of the blues and to merge all twelve bars into one cohesive form.

Honoré Dutrey plays the same melody again in the fifth and in the final chorus. He also plays this very same melody in a different tune recorded on the same date called Chimes Blues . For the purpose of analysing the connection of the performance with the copyright deposit, we can hence disregard this voice since it is merely a counterpoint that is used in any blues form.

Figure 2 Trombone chorus 1 and 2 (transcription by the author).

The Clarinet

The clarinet plays mostly above the lead cornet voice of King Oliver (see fig. 3). Mostly organised as arpeggios with neighbouring chromatic approaches and passing tones in variable phrase lengths, it resembles what will in the Swing era become the practice of improvised solo. The connection to the copyright deposit is limited to the use of the chromatic approach D sharp to E. Even though this is also part of the copyright deposit, this simple melodic tool is applied here as a chromatic approach on the rhythmic level of eight notes and should not be regarded as a characteristic motive of Dipper Mouth Blues (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 Clarinet chorus 1 and 2 (transcription by the author).

The Cornet Duo

To analyse the connection of the copyright deposit with the recording I therefore concentrate on the duet of the two cornets. The bandleader King Oliver was positioned closer to the recording funnel to ensure his lead position in relation to Louis Armstrong, and his voice is always above that of his duo partner, its range reaching a third higher. 17 Together, they fulfil the role of presenting the melody.

The Modular Counterpoint

Definition

I would like to introduce the term ‘modular counterpoint’. It is a system that functions like a mobile. In this kinetic sculpture there are several objects usually hanging from strings, balanced in equilibrium. It is constantly in movement and never reappears in the same state. The objects constantly change their position; sometimes they are close to the observer and clearly discernible, sometimes further away, sometimes partly or completely hidden by another object. The objects of the mobile are called cells and are assembled in a variety of ways and places within the form.

In modular counterpoint, independent voices connect cells to a continuous melody. Each individual voice is constructed autonomously, resulting in a contrapuntal relationship between the voices. The degree of elaboration and the position of the cells is not fixed, forcing the musicians to create a new constellation of cells for every new performance.

Analysis

The two cornets are organised by modular counterpoint. In this example, the cells are distributed on two voices, the two cornets. In the individual voice, the distinguishable cells are connected melodically by generic material to form a continuous melody. In the combination of the transcription with the copyright deposit, as shown in figures 4 and 5, the two are arranged in such a way that the correlating bars are aligned.

Figure 4 Combination of the copyright deposit and the according measures of the transcription of the cornet duo, first head chorus, measures 5–16 of the recording (transcription and graphics by the author).

Figure 5 Combination of the copyright deposit and the according measures of the transcription of the cornet duo, second head chorus, measures 17–28 of the recording (transcription and graphics by the author).

There are two kinds of correlations between the copyright deposit and the transcription: small melodic fragments of two to three beats and single pitches positioned in structurally exposed places (like at the downbeat or the end of a phrase). This makes those fragments distinguishable as cells that can be moved around like modules.

In the second half of bar 5 (the first bar in fig. 4), Louis Armstrong plays the exact same quarter notes D sharp to E as found in the copyright deposit, which is the only verbatim correspondence found in the example. Most cells are conveyed slightly differently in the copyright deposit and on the recording.

In measure 6, where in the copyright deposit an E is notated, King Oliver plays an E flat. Louis Armstrong also plays the flattened third of the key, also known as the blue note, in measures 9, 10, 18, 21, and 22. In a mobile, such an effect occurs as a result of the different lighting and viewing angles of the objects due to their changing position.

Another instance of a different position of a cell is found in measure 5, where the third from C to A is played in simple quarter notes, while in the copyright deposit, it is notated with the inserted lower neighbour G to A in the second half of the first beat.

Other differences lie in rhythmic alterations and varying placements of the cells within the measure. While in the copyright deposit the cells are notated in chronological order, in measure 6 of the performance the two cornet players state two different cells simultaneously in the first half of the measure. Also, the cell that is notated in the second half of measure 3 and 4 of the blues form is always performed in the preceding first half of the corresponding measure by one of the cornet players.

The two cornet players sometimes split a cell between them. In measure 12 the end of King Oliver’s phrase is a C on the downbeat, and the start of Louis Armstrong’s next phrase on the second half of beat 3 is a G. These are the defining pitches of the melodic fragment in the correlating measure in the copyright deposit.

The cell written in the copyright deposit as a chromatic approach to E with an intermediate C in the first half of the tenth measure of the blues form is never played in this order. In both chorus 1 and 2 this cell is performed by King Oliver as C to D sharp to E in measures 14 and 26 of the transcription. In the first instance, he starts on the second half of the first beat; in the second chorus, he starts a whole beat earlier.

The modular usage of the cells does not always result in contrapuntal music, but sometimes also in short phases of unison of the two cornet voices. In measure 11 of the transcription, the eighth notes D sharp to E are even followed by a G in unison. At the beginning of the second chorus, the unison lasts for the duration of the whole measure. This occurrence differs from measure 20, where cell C to B flat is performed simultaneously in different variations. King Oliver, after starting the cell two beats later, omits the chromatic passing tone B and arrives at the B flat a whole beat after Louis Armstrong. All instances of short unison continue in a similar way, with King Oliver always continuing at a higher pitch than Louis Armstrong, asserting his role as bandleader.

The root of the tonality, prominently stated as a quarter note tied to a whole note in the last two measures of the copyright deposit is eluded at the end of the first chorus in the recording, but used in the pick-up for the second chorus one octave higher by King Oliver. After the second chorus, Louis Armstrong ends the second head chorus with the root in the lower octave, whereas King Oliver ends on E with a preceding D sharp. Together, both players split the last cell between them, notated as D sharp, E, C in the copyright deposit. This brings the dyad of the two choruses stating the head twice to an end.

These detailed observations on the occurrences of the cells in the performance show that the cells are active in both players. In the process of assembling the performance, they are altered by dislocating them in time, altering them rhythmically, using them only as a pitch reference and connecting them with improvised lines of non-thematic content. The resulting experience of the music is controlled by the way the cells are arranged, and the listener follows the change between different states of the cells and their handling.

Classification of the Notation

Consideration of Available Classifications

The term ‘lead sheet’ is not suitable to categorise the notation of the copyright deposit of Dipper Mouth Blues . In Jazz, this term is commonly used to describe the notation of a simplified melody with chord symbols of a tune as information for accompanying instruments and improvising soloists. It is used by the composer or bandleader to communicate the tune to a group of musicians in rehearsal and can also be used as memory support on the bandstand. ‘Lead sheet’ was also the legal term for a copyright submission before 1972. 18

While the copyright deposit of Dipper Mouth Blues is indeed a lead sheet in the pre-1972 legal sense, it is not a lead sheet in the sense an active jazz musician would expect, intended to also serve as a playing score. If one were to apply this copyright deposit as a lead sheet in the sense of a playing score, the mechanics of the modular counterpoint would not fall into place, and the written melody would be heard throughout the head performances. The result would therefore lack essential characteristics of the tune’s original recordings. The practice of generating a lead sheet by simplifying a transcription of a recording would in this case result in a completely different result. Other possible definitions like blueprint, or prototype, after which the following performances are to be modelled, would not suffice to describe the copyright deposit of Dipper Mouth Blues .

The notation categories described above all assume a hierarchy between notation and performance based on chronology. The lead sheet is modelled either after one or several performances, or after an individual composer’s work. The copyright deposit of Dipper Mouth Blues, however, is based on a different context in which the source of the sheet music and the performances are the same, rather than chronologically following one another. Existing surveys of an array of copyright deposits of early jazz show the history and connection of sheet music and performances. 19 These valuable sources can be used to expand the discussion of my terminology to include more examples of that time. I turn to the concept of the archetype according to C.G. Jung in order to find a suitable terminology for the observations regarding Dipper Mouth Blues .

The Concept of the Archetype According to C.G. Jung

Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung engaged at length with the concept of archetypes. He defines the term as follows: “The archetype is essentially an unconscious content that is altered by becoming conscious and by being perceived, and it takes its colour from the individual consciousness in which it happens to appear.” 20 Archetypes can be figures, such as the sage, the mother, but also the element of water, or the shadow. Any list of archetypes is by no means conclusive and can be further expanded.

Jung continues to note that the unconscious content is part of a collective unconsciousness that does not “owe its existence to personal experience and consequently is not a personal acquisition.” 21 He makes clear that “the contents of the collective unconscious have never been in consciousness, and therefore have never been individually acquired, but owe their existence exclusively to heredity.” 22 Relating to the mechanics between our consciousness and the archetype, Jung postulates that “the collective unconscious consists of preexistent forms, the archetypes, which can only become conscious secondarily and which give definite form to certain psychic contents.” 23

The Notation of an Archetype

Through the analysis of the cornet duo and its connection to the copyright deposit we discovered the concept of modular counterpoint, whose cells can be found in the copyright deposit as well as in the performance of the cornet duo. In the performance, they appear in different states of articulation. Sometimes, as in measure 6 of the blues form, only the top note of the copyright deposit can be found in the performance, which leads to the conclusion that the writer of the copyright deposit just copied the measure before filling the space. In the notation, the possibilities of alterations of the cells are omitted and only the bland version of the cells is stated, similar to a two-dimensional sketch of a three-dimensional piece of art. In the copyright deposit, those cells are assembled in an orderly way, like in a type case a printer would have had in front of him to put together a printing plate for a mechanical letterpress.

The technique of modular counterpoint lets the Dipper Mouth Blues come into existence even when some parts are missing. In the copyright deposit, there are no areas where thematic material is skipped or blurred and cells are connected with improvised material, a manipulation that is typical to the performances. In the performances, the density of the application of cells varies from chorus to chorus.

Both the copyright deposit and the recording are instances where something in the collective unconsciousness nourished the apparitions of the tune which is the source of those manifestations. This is an archetype, an unconscious content of Dipper Mouth Blues, which is altered through the consciousness of the people involved, and subsequently becomes part of our conscious world. Each manifestation takes its colour from the individual consciousness in which it happens to appear, in this case from the author and copyist of the copyright deposit or the individual musicians involved in the recording.

The archetype, which is the source of its manifestation, is located in the unconscious. Therefore, it is not possible to clearly define the characteristics of the archetype. However, it is possible to speculate, based on the observations in the analysis, on the archetype of Dipper Mouth Blues . The complex contrapuntal structure requires that musicians are completely aware of their surroundings and pay attention to a constantly changing reality. Since King Oliver and Louis Armstrong negotiated the counterpoint anew for each performance, we can retrace how the two cornet players would mediate in real-time. The practice of modular counterpoint gives both cornet players equal responsibility to mold the cells into the theme. Therefore, the archetype of Dipper Mouth Blues is a source of innate listening, collaboration, considerate action taking and the will to come to terms starting out from a blank slate each time around.

In the common use of lead sheets, we assume a chronological hierarchy either from writing to performance or from performance to writing. This is not the case here, and the term archetype enables us to see all the manifestations of Dipper Mouth Blues as secondary to a form that is common to all manifestations. Because an archetype is not a personal acquisition, but owes its existence to heredity, it can be the source of inspiration to anyone connected to that archetype. On the other hand, the execution of the tune’s pitches does not let the archetype become unequivocally conscious. A performance or a notated score needs to tap into something deeper than pitches, something in the unconscious of human beings.

Furthermore, the oddities of missing accidentals as described in the analysis of the copyright deposit would be considered mistakes if the copyright deposit were a lead sheet. In the notation of an archetype, these inaccuracies are merely part of the colour that is given to the archetype by the author.

Conclusion

The comparison of the transcription of the recording and the copyright deposit of the tune Dipper Mouth Blues raises the question about the category of notation they belong to. The copyright deposit cannot be categorised as a lead sheet in the common sense of a performing score or a simplified transcription of a performance. Musical analysis shows that the concept of modular counterpoint is prevalent in both the performance and the copyright deposit. This leads to the conclusion that they are both manifestations of an archetype. With archetypes, a concept by psychiatrist and psychoanalyst C.G. Jung, a pre-existing form becomes conscious and takes its colour from the individual consciousness in which it happens to appear. Modular counterpoint enables the individuals to colour this archetype in different ways, resulting in different forms of manifestations. The copyright deposit therefore is a notation of an archetype .

References

- Allen, Walter C. (1987), “King” Oliver , Rev. ed. by Laurie Wright, Chigwell: Storyville.

- Anderson, Gene (1994), “The Genesis of King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band”, in: American Music 12, no. 3, 283–303. https://doi.org/10.2307/3052275

- Anderson, Gene (2007), The original Hot Five recordings of Louis Armstrong, Vol. 3, CMS Sourcebooks in American Music, New York: Routledge.

- Bergreen, Laurence (2000), Louis Armstrong: Ein extravagantes Leben: Eine Biographie, deutsche Erstausgabe, Zürich: Haffmans.

- Brothers, Thomas (2012), Dipper Mouth Blues, Video, retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/webcast-5624/ (4.6.2021).

- Brothers, Thomas (2014), Louis Armstrong, Master of Modernism, New York: W.W. Norton.

- Chevan, David (1997), Written Music in Early Jazz , PhD dissertation, City University of New York.

- Dodds, Baby (1959), The Baby Dodds Story. As Told to Larry Gara , Los Angeles: Contemporary Press.

- Jung, C. G. (1969a), “The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious”, in: The collected Works of C. G. Jung, Vol. 9, London: Routledge & Kegan, 3–41.

- Jung, C. G. (1969b), “The Concept of the Collective Unconscious”, in: The collected Works of C. G. Jung, Vol. 9, London: Routledge & Kegan, 42–53.

- Kernfeld, Barry Dean (2006), The Story of Fake Books: Bootlegging Songs to Musicians (Studies in Jazz, Vol. 53), Lanham: Scarecrow.

- Library of Congress. Copyright Office (1923). Catalogue of Copyright Entries, Part 3: Musical Compositions, New Series, Vol. 18, No. 1, Washington: Government Printing Office.

- Schuller, Gunther (1968), Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development , New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/3392329

Discography

Henderson, Fletcher (1960), The Fletcher Henderson Story: A Study in Frustration , LP, Columbia CL-1682.

Oliver, King (1974), The Great 1923 Gennetts , LP, Herwin H-106.