Transición II by Mauricio Kagel

“The most suitable form of writing for each compositional circumstance”

The work as human action (genesis) is productive as well as receptive. It is continuity. Productively it is limited by the manual limitation of the creator […]. Receptively it is limited by the limitations of the perceiving eye. […] The eye must “graze” over the surface, grasping sharply portion after portion, to convey them to the brain which collects and stores the impressions. The eye travels along the paths cut out for it in the work.

Paul Klee, Pedagogical Sketchbook (1925)

Writing in Composing 1

In the act of writing, compositional intentions can be manifested in a visual and material form on a two-dimensional surface. This rather simple statement becomes especially complex if one considers forms of writing within an entire creative process, where not only the intentions but also the exploratory activity to achieve them are developed by means of writing strategies. In the transition from purely mental ideas to visible inscription, the functions of different types of writing seem to be aimed not so much at purposes of communication or archiving and transmitting, but rather at cognitive and knowledge-generating compositional operations driving the development of the composition.

These preliminary hypothetical considerations provide the starting point for this essay’s central question, which is to investigate how some graphical forms stemming from the creative process of Mauricio Kagel’s (1931–2008) Transición II for piano, percussion and two tapes (1958–59) 2 become first and foremost devices to support compositional thinking, enabling explorative and operative compositional practices.

At the congress Notation Neuer Musik 3 in Darmstadt, a crucial moment for the reflection on new ways and possibilities of musical notation, Kagel gave a lecture entitled Komposition – Notation – Interpretation in whichhe explained with explicit reference to Transición II how the composition “forced [him] gradually to develop an extensive system of signs, symbols and new notation techniques in order to be able to write down precisely [his] ideas. Clearness or ambiguity did not play a particular role at first; what was essential was to find the most suitable form of writing for each compositional circumstance and to define and classify this form”. 4

In his research into the most appropriate forms of writing, Kagel therefore critically confronts himself with different notational typologies that are strictly connected to the compositional practices of more or less recent musical traditions and his musical experiences. In his modus operandi – meaning the ways in which Kagel realises his “composership” 5 – appear, for example, number tables to apply the serial principle, rotatable objects creating an aleatoric graphic score, and diagrammatic structures influenced by his musical experiments at the Studio for Electronic Music of the West German Radio. Exploring Kagel’s use of different writing forms and materials (including paper typologies) thus permits to trace the “metamorphosis of the ways of creation” 6 – to use the words of his colleague György Ligeti – and his critical elaboration of new tendencies in composing and writing music.

Tracing the Process

The theoretical framework of this study draws on interdisciplinary approaches, which on the one hand bring to light the most diverse and hitherto little observed aspects of writing 7 , and on the other hand focus on the creative process with its often non-linear, sometimes erratic, chaotic, unpredictable course 8 preceding the final form of a work.

A change of perspective with regard to writing (meant in a broad sense and not specifically implying musical writing) is suggested by philosopher Sybille Krämer’s studies on ‘notational iconicity’ ( Schriftbildlichkeit ) and ‘operational iconicity’ ( operative Bildlichkeit ) aiming to revise the so-called ‘phonographic dogma’ under which writing is merely a “fixed version of spoken language”. 9 Krämer on the other hand proposes an integrative concept of writing 10 including various types of writing practices (e.g. mathematical calculation, diagrams, tables, graphics, lines, scientific formulas, music or dance notations, etc.) 11 Considering the “(almost) forgotten dimensions of writing”, 12 she focuses on the visuality of written texts (in their hybrid nature, both iconic and linguistic), their “two-dimensional spatiality”, and also their “operability”. 13 Forms of writing indeed support thinking processes and “open up a neatly arranged and controllable space [ Operationsraum ] 14 of aesthetic presentation and tactile manipulations”, 15 in which cognitive processes become clearly visible through their externalisation in visual representations.

Considering the initial hypothesis within the framework of this theoretical perspective, it is now possible to specify that ‘writing music’ could be understood as an expanded and broader concept including all graphic strategies in the composer’s practices to shape, develop and supervise a work, to enable the exteriorisation of cognitive processes for the realisation of operative compositional practices, and to experiment and find new and more adequate representations of musical ideas. However, the expression ‘musical notation(s)’ is used here to refer only to the final written forms of a composition as fixed in the score.

As this study focuses particularly on the heterogeneous manifestations of writing in the compositional development of a work, further methodological clarification is required regarding the direct examination of original sources – i.e., the traces of the process.

Examining primary documents (of whatever type) always raises the philological question which methods are appropriate in the research process. 16 Particularly revealing with respect to the study of Kagel’s manuscripts for Transición II is the approach of genetische Textkritik proposed by Bernhard R. Appel and pursued within the Beethovens Werkstatt 17 research project. A sub-discipline of music philology, it is rooted both in methodological contributions of the French literary ‘genetic criticism’ (or critique génétique) 18 and musicological sketch studies. The consideration at the basis of the ‘genetic criticism’ – later transferred to other disciplines – is that the ‘process’ and not only the outcome should be at the heart of the research. From this perspective, Appel contemplates how compositional ideas are reflected in writing processes so that every trace of the work’s development gains value in and of itself, as opposed to considering merely the final product. Hence, through an almost archaeological procedure, musicological genetische Textkritik maps the “paths of compositional thought”. 19

An Insight Into Transición II

In the autumn of 1957, about a year before beginning to compose Transición II , Mauricio Kagel moved from Buenos Aires to Cologne with his wife, the sculptor and graphic artist Ursula Burghardt. Thanks to a scholarship from the German academic exchange service (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst, DAAD), he was able to work at the West German Radio Studio for Electronic Music (Westdeutscher Rundfunk, WDR) and attended courses in phonetics and communication theory given by Werner Meyer-Eppler at the University of Bonn. Having introduced himself in a letter to Wolfgang Steinecke (who at the time was director of the Darmstadt Summer Courses) he was immediately offered the opportunity to present the premiere of his Sexteto de cuerdas (1953, revised 1957) at the 13th edition of the Summer Courses in 1958, an occasion which would serveas a catalyst in establishing himself as a composer of high repute within the Darmstadt circle.

At the time, the European post-war avant-garde at Darmstadt strongly identified with serial thinking. In order to establish himself in this rather closed context, 20 Kagel worked intensively according to serial principles, though constantly remaining open to new musical paths and experimental suggestions, such as the revolutionary wave that John Cage unleashed in 1958, contributing “to the collapse of the modern serial myth” 21 with his compositional principle of aleatory, as Kagel expressed himself in his article John Cage en Darmstadt 1958 . The serial thinking rooted in Darmstadt and new inspirations from overseas found a point of intersection in Transición II, the first work Kagel composed entirely in Europe. 22

This highly experimental composition requires a pianist to play on the keyboard, while a percussionist produces sounds directly on the body and the strings through various actions a striking reference to John Cage’s ‘prepared piano’. In contrast to to the latter, however, Transición II requires real-time preparation during the performance. 23 The close interaction of the two performers, following the composer’s directions, produces an accidental or latent (rather than programmatic) form of theatricality that Kagel would revisit in later compositions.

In addition, the ensemble includes two tape recorders reproducing sound materials of the performance, either pre-recorded – sometimes with electronic modification (tape I) – or recorded during the performance and played back at a later time according to certain rules (tape II). The pioneering idea of realising a live-electronic music of sorts, despite the technical difficulties this presented at that time, is a result of Kagel’s compositional search for the expansion of possibilities of a single instrument. Indeed, all the piano’s he sonic possibilities are explored, and the electronic medium further amplifies (or rather doubles in its echo reproduced by loudspeakers) the expansion process, as if it were at the service of this eminently instrumental experimentation. The electronic medium is used primarily for instrumental, non-electronic experimentation. It seems that its function is to serve sound experimentation on and with instruments.

The high complexity of this composition is already evident from the 14 (of the total 43) trilingual pages of performance instructions, considered by Kagel “as a necessary evil and as a further symptom of the underdevelopment of traditional means of notation.” 24 The instructions are divided into ‘Directions’, ‘Performance Notes’, ‘Explanation of Symbols’, and ‘Nomenclature’. There he clarifies the organisation of the piece into 21 sections, each having a specific type of structure indicated by the letters A, B and C; in total there are nine A structures, seven B structures and five C structures. 25 In preparing the piece, the performers may select 21 sections, the condition being that the minimum duration of the entire piece is 10 minutes. Additionally, Kagel indicates that each section is to be played in its entirety and only once. The order of their arrangement is arbitrary; however, the performers are subject to several further directions that limit their freedom as ‘co-composers’.

The premiere of Transición II took place during the 14th Summer Courses in Darmstadt in 1959 with Mauricio Kagel at the piano and Christoph Caskel on percussion 26 and received remarkable acclaim. In the same context, it was performed three times within a week, 27 and Karlheinz Stockhausen even dedicated a lecture to the it in his lecture series Musik und Graphik. Kommentare zu neuen Partituren . 28

In concluding this brief insight into Transición II , it should be mentioned that in it, Kagel intended to explore the continuous possibilities of transformations of compositional material, as the title programmatically illustrates. In his article on Transición I for electronic sounds (begun in 1958 at the West German Radio Studio for Electronic Music and completed only two years after Transición II) Kagel explained that even at that point he had already been interested in the principle of transition ( Übergangsprinzip ). 29

The emergence of a musical form, without a predetermined itinerary, interested me. The large-scale form – indeterminate in the contexts of changes and technical processes – which was to be responsible only for a general principle of transition (transición), had to show itself as an open field for a continuous transformation of the material and the subsequent constantly renewed relationships. 30

The non-predetermined development of a musical form should thus create an ‘open field’ for continuous transformations of the material. As Pia Steigerwald points out, this theoretical principle is present in Transición II on all compositional levels:

Form through sectioning and a tendency toward the open; structure as the generation of structural types to be combined according to certain rules; material as a category depending on formal and structural processes as well as on sound production; sound as the interaction of the two performers, who influence each other with fixed roles (the pianist as a keyboard player and the percussionist as a string player). And finally, the musical notation as a mixture of action- and result-notation, as well as graphic notation. 31

The heterogeneous catalogue of different experimental, graphical, and notational tendencies represents one of the most interesting aspects of this work.

Focussing particularly on forms of writing that preceded the final score, four moments from different phases of the creative process of Transición II will be investigated: the structuring of number tables, the building and manipulation of discs, the drawing and thereby visualisation of a graph, and finally, the fixing of lines.

Visual Strategies as Operative Devices

1. Structuring of Tables

Only a small part of compositional thinking is recorded in writing – mostly that which is difficult to remember or to work out purely mentally. From this small part, written elements can take on a compositional and functional form only in a precise graphic representation. This is the case with the tabular arrangement of tone rows, a typical form for the determination of material within the framework of twelve-tone technique, 32 which allows the composer – normally at the beginning of the compositional process – to arrange, visualise, and select from the combinatorial possibilities of the musical material so that all twelve notes are played before any recurrences.

The rich portfolio of documents relating to Transición II , preserved in the Mauricio Kagel Collection at the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel, consists of six folders. The first pages, archived under Erste Versuche Gedanken Skizzen (first attempts, thoughts, sketches), are followed by 30 pages of squared paper – some dated, some with references to page numbers of other notebooks – in which Kagel predisposes a catalogue of number tables in order to write down pitch rows and their permutations.

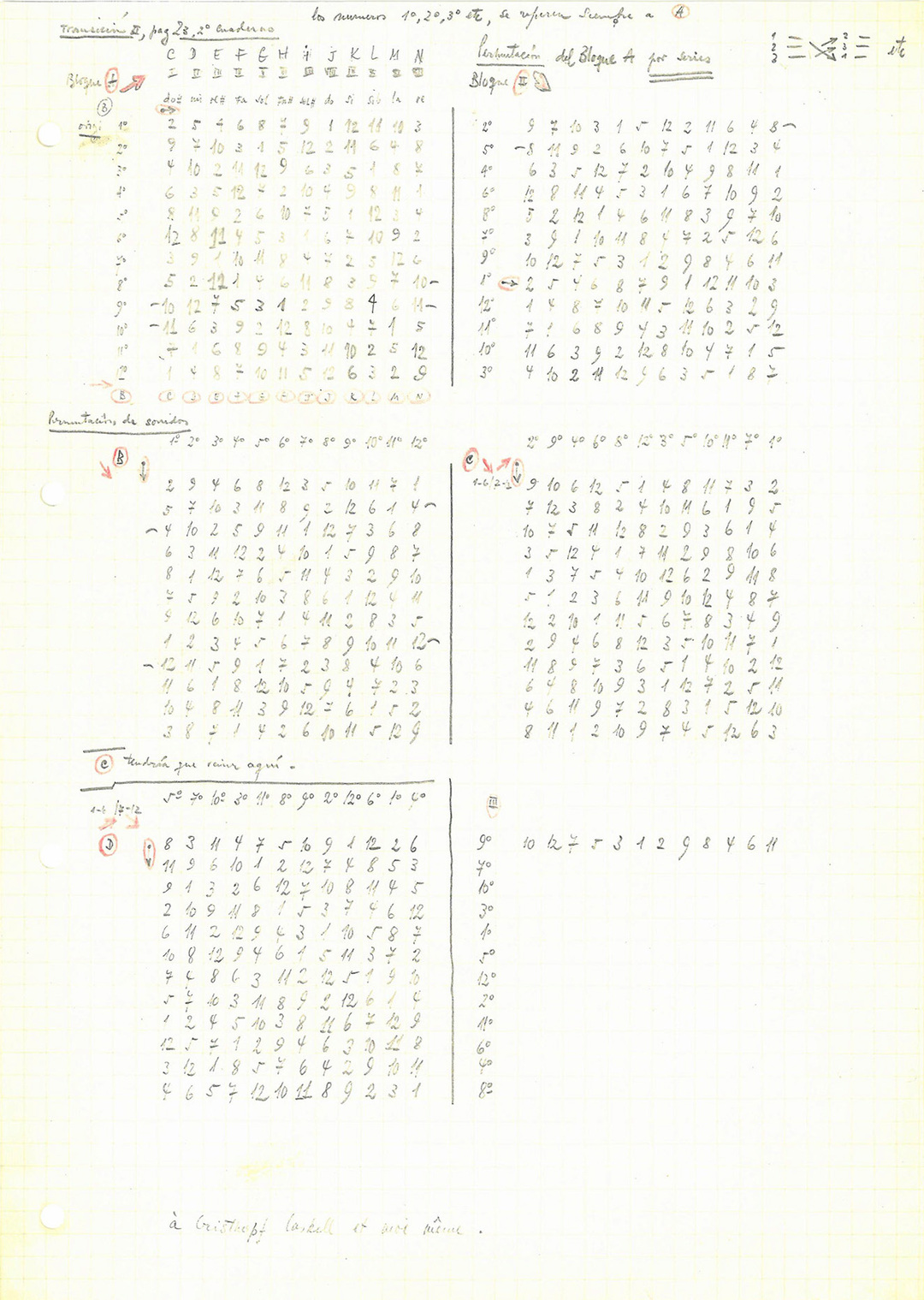

Figure 1 shows a page with six tables of tone rows, the last of which is only partially sketched. Each number of the rows corresponds to a note of the chromatic scale (C = 1; C sharp = 2; D = 3; D sharp = 4, and so on). In the first table (marked with A), the twelve-tone rows are indicated with ordinal numbers, arranged vertically from 1o to 12o. The following tables do not include any row permutation but represent the same twelve-tone rows (i.e. the identical sequence of notes) in different positions on the table. 33

How and at which later stages of the work’s creation the tone rows and their arrangement in tables were used remains vague. What is interesting here is not so much the discovery of an application of this meticulous preparatory work in the final score (which has often been pursued in philological research). Apart from a teleological reconstruction, this compositional moment allows to observe how the table as a graphic object with a precise order of the elements (i.e. numbers in boxes corresponding to established pitches, sorted according to a certain logic, with arrows indicating the possible reading direction) allows the composer to set up a continuum of possibilities and then select his own musical material.

Kagel’s thorough work on the serial arrangement of pitches is a confirmation of his intention – at least at this point of the creative process – to elaborate his work in a serial manner. One has, however, to keep in mind that “most of the piece [in the final score] is in approximate notation with respect to both pitch and rhythm, making a serial control of these parameters impossible”. 34 As Attinello writes, Transición II represents an “elaborate presentation of ‘subverted’ serialism”, because of “the combination of a hyper-difficult performance score with arbitrary operations”. 35

Regardless of the result of this compositional work in the printed score, the great effort Kagel obviously put into the elaboration of the numerous pages of tables testifies yet to something else: it manifests not only the intention to compose according to serial principle but also implicitly reveals the wish and search for legitimation of his work as a composer within the Darmstadt circle where serial thinking ruled, even over compositional writing practices.

Figure 1 Page of squared paper with six tables of tone rows, the last of which is only partially sketched, related to Transición II . Mauricio Kagel Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel.

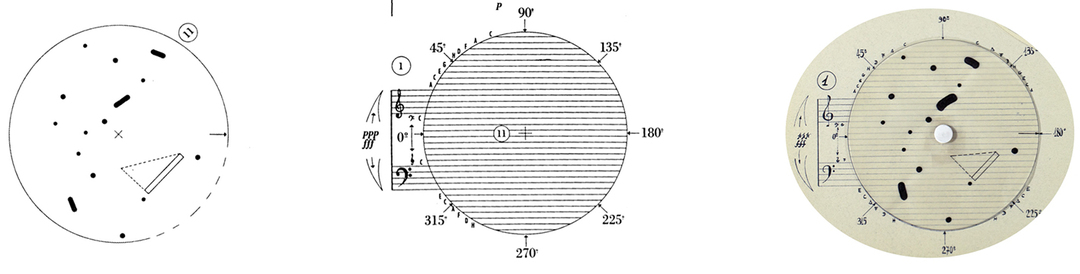

2. Manipulation of Discs

While tables of tone rows can be considered a rather conventional type of writing for composers participating in the Darmstadt Summer Courses, the rotatable discs that Kagel conceived for the aleatoric sections of Transición II are quite particular.

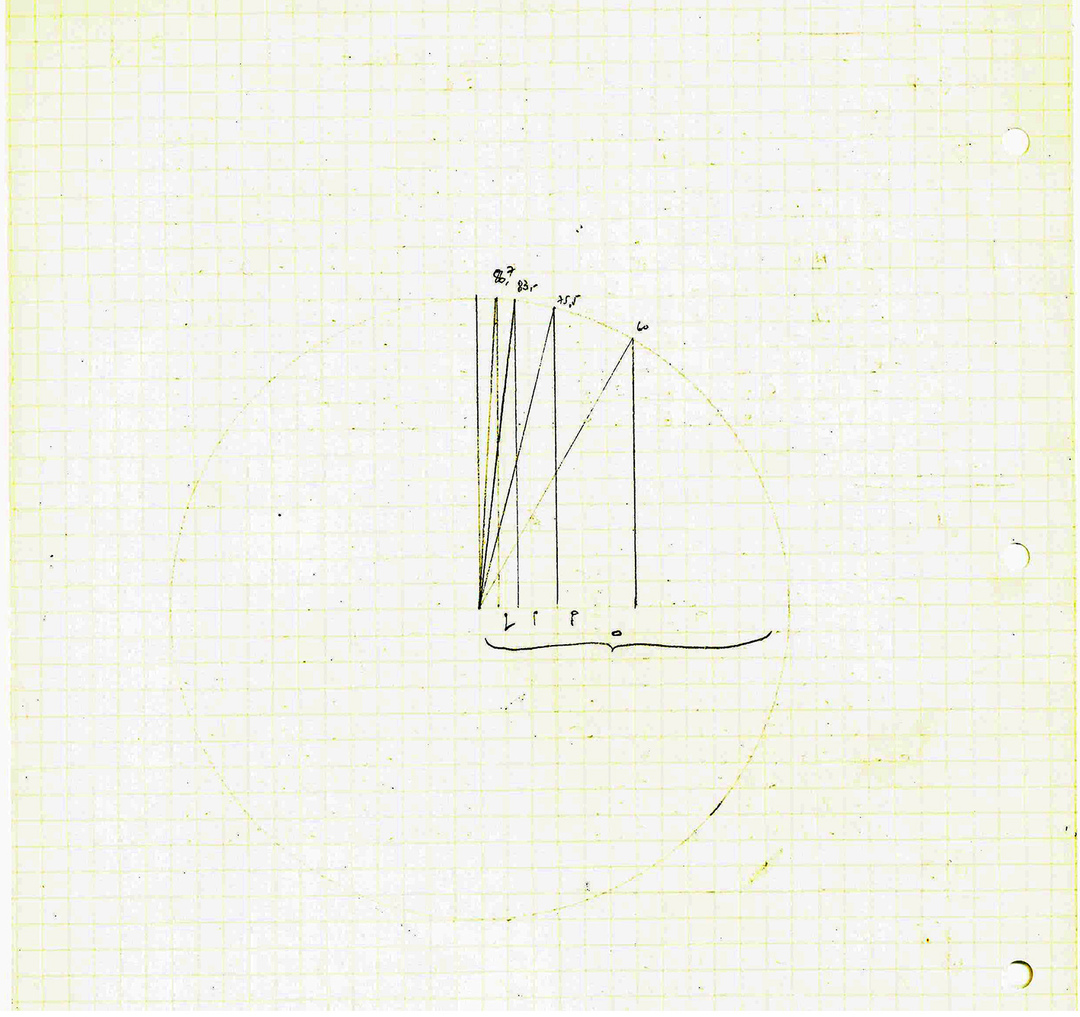

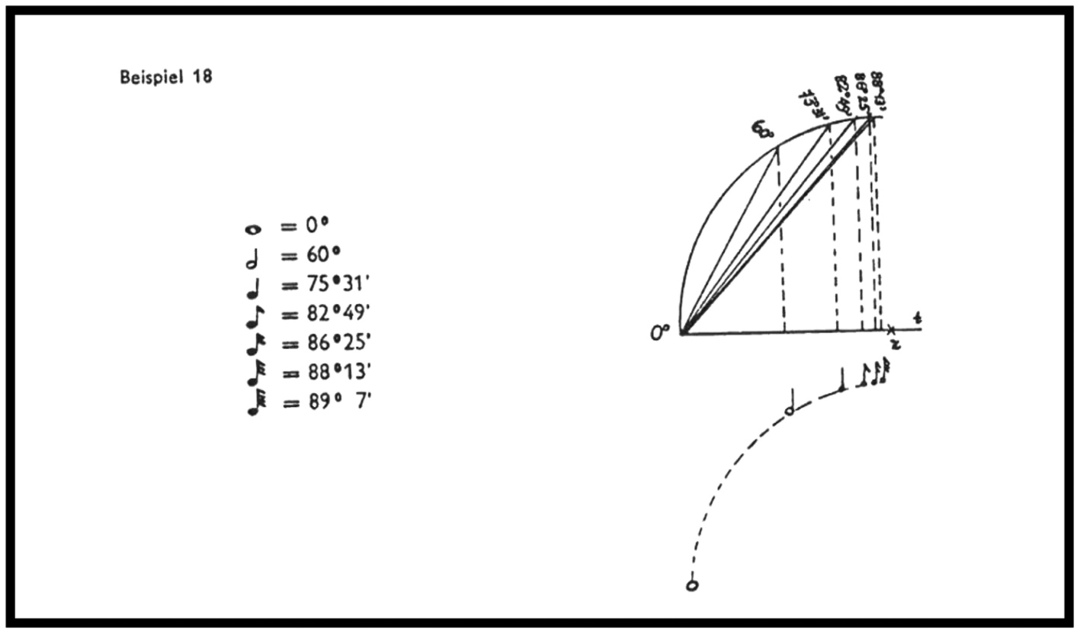

On the back of one of the squared pages containing the tables, Kagel sketches a circumference (its centre in the origin of two axes of a Cartesian plane) and some of its radii. Additionally, he indicates the widths of the angles (80,7° – 83° – 75,5° – 60°) formed between each radius and the perpendicular from the point of the intersection of this radius with the circumference and the abscissae axis (the radius set at 180°). These widths correspond to specific tone durations (eighth note, quarter note, half note, whole note), as indicated above the brace (fig. 2).

This representation provides a first sketch for a graphic example (“Beispiel 18”) printed in Kagel’s article Translation – Rotation 36 (fig. 3), where in a caption he describes the relationship between the width of the angles and the duration of the notes more precisely. In this theoretical text, Kagel explains in detail two new compositional principles for which any musical configuration can be transformed through geometric permutation by rotation (of which some elements are described above) or by linear displacement, i.e., translation.

Figure 2: Sketched circumference with radii and widths of the angles on the back of a page containing the tables related to Transición II . Mauricio Kagel Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel.

Figure 3 Example n. 18 from the text Translation – Rotation by Mauricio Kagel (Kagel 1960, 43).

The conception of these principles was most likely influenced by the reflections “in the field of becoming form” 37 contained in Paul Klee’s Das bildnerische Denken 38 which has influenced the thinking of quite a few composers. Kagel points out that the musical translation from the purely graphical origin of “structural processes” and “form principles” must remain a rather “individual and almost ‘private’ affair”: From a mere “pictorial thought”, it is not immediately possible to elaborate a “musical application”: this can only occur if the “arrangement and manipulation of the material” is renewed and reformulated. 39 With the disc structures for Transición II, Kagel realises exactly this shift from a visual inspiration to an operational tool to externalise and fix his theoretical and compositional ideas, but also to generate and develop a sonic reality.

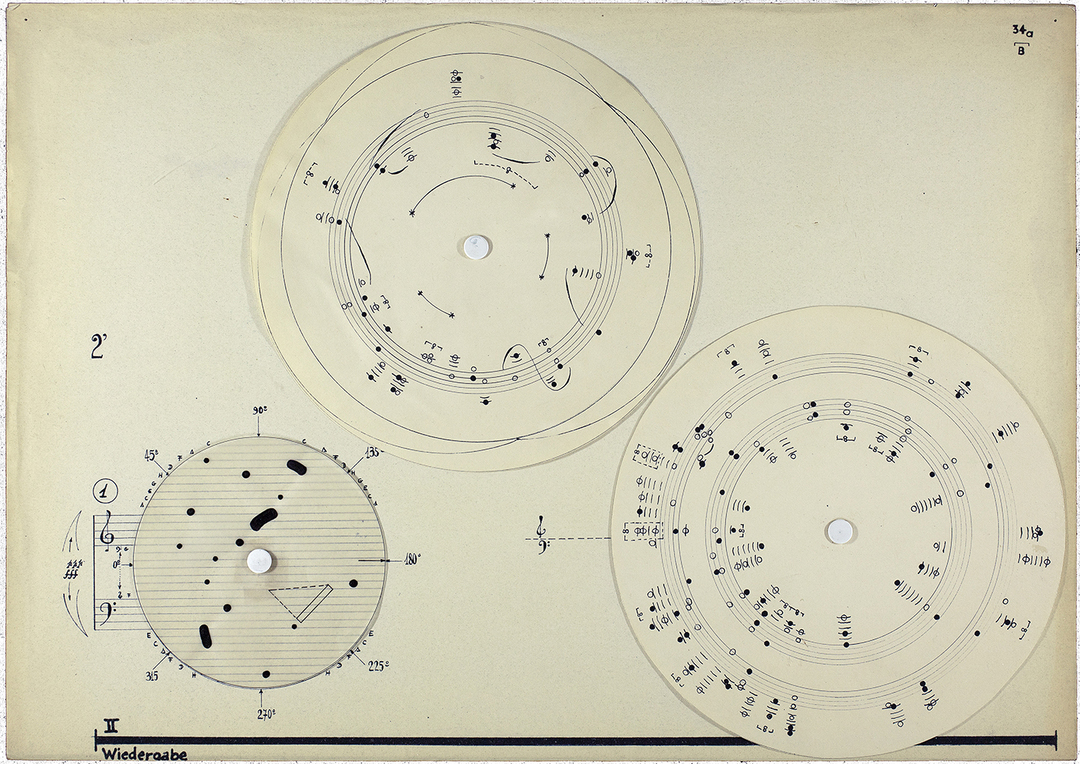

The collocation of the sketched circumference with radii and widths of angles in what was probably the first genetic phase of the compositional process of Transición II suggests that the theorising of the ‘rotation principle’ is firmly connected to this work. In its final score, the principle is indeed applied significantly by means of different types of rotatable discs. I now turn to a page from the autograph score written by Kagel and most likely prepared for the performance or the final fair copy (fig. 4). What we observe is a score ‘manipulated’ by the performers, who have cut the discs (provided on another page) and fixed their centres in order to rotate them. 40 The geometric configuration of the figures is detached from its relationship with a system of coordinates that definitively determine the value of each element. The figures’ rotation movements establish new coordinate systems, thus each time determining new musical values. In reference to these structures to be performed by the pianist (in the autograph score on page 34a[B], but in the final score the page number changes to 26a[B]), 41 Kagel explains that “[e]ach disc is to be played twice, but in a new position each time. One has to begin with the disc 1 [the first one on the bottom left]; afterwards the succession of the discs is ad libitum.” 42 Moreover, the signs on the discs must be read from left to right, and those that appear superimposed vertically must be played simultaneously. 43

Figure 4 Page 34aB from the autograph score of Transición II used for the performance (in the printed final score it is page 26aB). Mauricio Kagel Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel. © Mit freundlicher Genehmigung der Universal Edition AG.

Looking in particular at the disc labelled ‘1’ (fig. 5), we can observe that some dots and some elongated dots are written on a transparent, rotatable paper disc, under which is a fixed musical staff: “[t]he upper system of each semi-circle is to be read in treble clef, the lower one in bass clef”. 44 The pianist must choose where to rotate the disc, however, only within the pre-set eight positions, i.e., only in the angles where the arrow drawn on the disc meets one of the arrows on the page. The letters written in the four circular swells indicate the names of the notes for clarity. By rotating the disc, the notes (dots) or clusters (elongated dots) move upwards, thus becoming higher, and should be played increasingly piano ; conversely, those that turn downwards become lower and are to be played increasingly forte . The rhythm, however, results from the horizontal distance between the signs. 45

Figure 5 . On the left: the disc to be cut out and then fixed with a slit pin on the disc (shown in the middle) at the ✛ sign. (Both figures are taken from the published score of Transición II : Kagel 1963a, 44 and 28). I digitally rotated the first disc to have the same degree of rotation to compare it with the disc on the right taken from the autograph score for the performance (see fig. 4). Mauricio Kagel Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel. © Mit freundlicher Genehmigung der Universal Edition AG.

In Transición II , writing music does not so much entail the fixation of a specific musical idea but rather the predisposition of materials, objects, and rules for their basic functioning to be manipulated in order to generate an aural event that may remain unknown to the composer. With the handling of the musical text in this specific mobile form, Kagel attempts to shift the act of composition far beyond the finished score and to pass this task on to future performers. Somehow, the compositional process expands with time, the work remaining a ‘work in progress’. 46 With this almost playful strategy, Kagel allows the performers to become co-authors of the composition with each new performance. This is in line with Kagel’s own theorising in his text Translation – Rotation, where he writes that “interpretation is then a field of composition, both when it manifests itself during the performance as an extension of the idea, and when the perspective of infinite interconnections of the inner articulation of form requires an interpretative treatment of the material”. 47

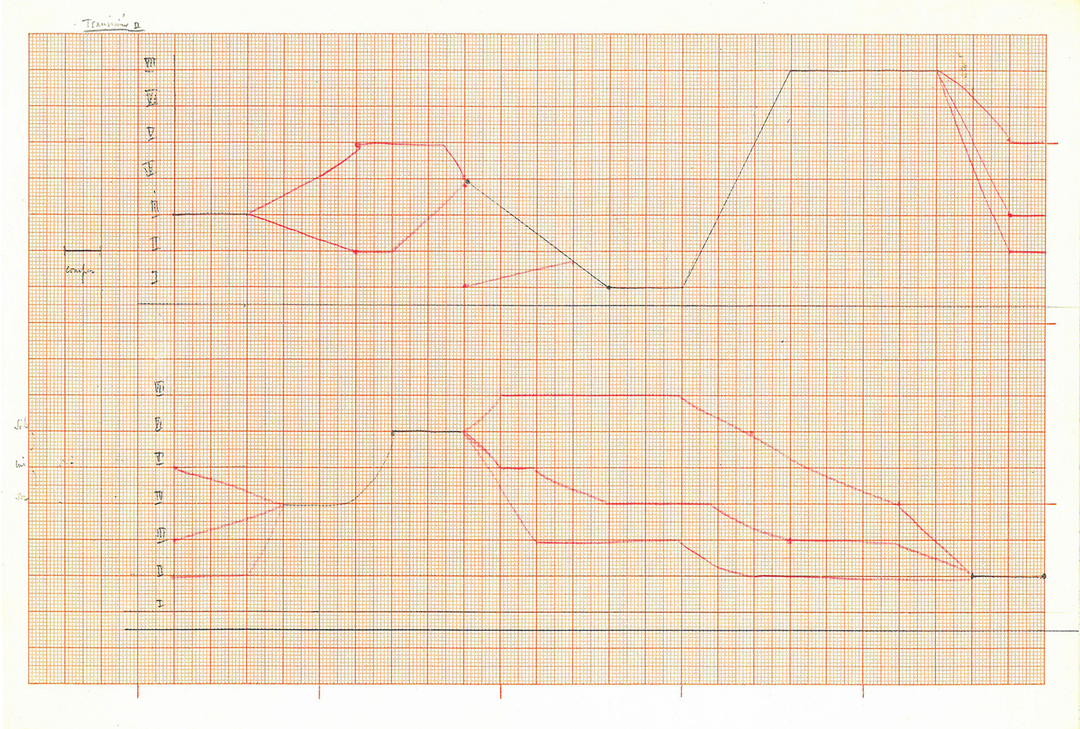

3. Visualisation Through a Graph

Through spatial coordinates, a diagrammatic figure becomes, as Sybille Krämer explains, an “operative medium […] as a result of an interaction within the triad of imagination, hand, and eye”. 48 The graphical structures sketched by Kagel on milimetre paper (fig. 6) and conserved in the manuscripts related to Transición II can be considered as graphs facilitating for the composer and performers the quick and effective visualisation of the metronomic tempo’s variations. The only textual information in this manuscript is a small caption in Spanish indicating that each horizontal centimetre on paper represents a measure ( compás ). The abscissa then indicates the course of time, while the ordinate, marked with Roman numerals from I to VII, corresponds, as inferred from a comparison with other manuscripts and the final score, to seven levels of metronomic speeds. Specifically, level I corresponds to 40 BPM, and level VII to 160 BPM. Courses are traced in black pencil and in red when different tempo paths overlap. However, the colour difference is not present in the corresponding pages (9A to 12A) of the published score.

The use of millimetre paper stands out as unique among the other paper materials used in the compositional process of Transición II , but looking at the sketches for Transición I (for tape), it is immediately evident that Kagel used very similar graphs on squared paper for that work. The genetic processes of these compositions are intertwined, even chronologically. The material correspondence between them, however, shows that Kagel was accustomed to using this type of paper and other such types of graphic writing, which could have been influenced by his experience at the West German Radio Studio for Electronic Music. As he writes in his article on Transición I , the influence of instrumental music on electronic music is revealed in the adoption and assimilation of methods and principles of compositional organisation. 49 What emerges from this moment in the compositional process is the possibility of observing how the experience in the studio also left traces on Kagel’s way of visualising sound in the context of an instrumental section of a mixed music work.

Figure 6 Graph relating to Transición II on millimetre paper. Mauricio Kagel Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel.

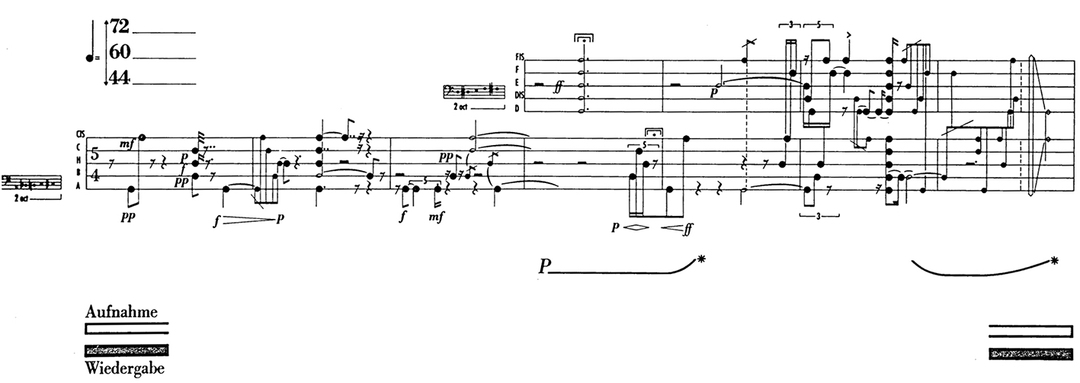

4. Fixing of Lines

When tape recorders became available to composers, they found themselves presented with the challenge of writing down a new form of sound production – i.e., the reproduction through loudspeakers of sounds recorded on tape – and in some cases, its interplay with sounds played live in front of the audience. Since the late 1940s composers had dealt with the notation of mixed music both in composition workshops and in electronic music studios, additionally reflecting on their ‘writing systems’ at various public and private events. 50 Kagel’s encounter with electronic music in the autumn of 1957 meant for him the introduction to a “new musical time” 51 . Working on his first electronic composition Transición I , he was interested in exploring the relations between musical material and its temporal formation. 52

Kagel’s reflections on temporality also manifest themselves in Transición II , in that two magnetic tapes on which structures are pre-recorded or recorded during the performance are also played back during the performance. In the introduction to the score, Kagel provides further clarification regarding the use of the two tapes: Tape I is for recording the B or C structures before the performance; Tape II is for recording the A or C structures during the performance. 53 The composer explains further:

The music stored on [Tape I] may be freely subjected to a number of processes altering timbre and wave form to a degree such that recognition of the original sounds is made impossible in the result. […] Unless it has been possible to arrive at a thorough transformation of the original piano sounds, Tape I must be restricted to simple reproduction.

The material to be played back on [Tape II] must have a duration equal to one half, one third, or one quarter of the originally recorded structures; but there must be no alteration either of the pitch or the duration of the original sounds. 54

In Transición II , the production of recorded sound using magnetic tapes before and during the performance together with live instrumental sounds generate three different temporal structures, which, as Kagel writes, are superimposed: the first is given by the actions of the two instrumentalists (direct performance), the second by the sounds on tape produced and recorded previously by the same instrumentalists, and the third is formed during the performance by recording certain segments of the piece, which are played back into the hall via loudspeakers (indirect performance). Three fundamental layers are thus developed in relation to time. 55

In the introduction to the score, Kagel suggests that the performers should attempt to simulate playing without producing sound when “taped material, not processed, is sounding alone without simultaneous live performance”. 56 With this idea, it seems that the composer intends to further confuse the acoustic perception of the audience, inducing fusions – or better ‘transitions’ – between different sound productions, and therefore between the three temporal structures.

In order to synchronise the three structures in the final score and thus to coordinate the interaction between the magnetic tapes and live performance, Kagel in some instances places lines at the bottom of the score. As can be seen in Figure 7, he also adds written indications in relation to the two lines such as “Aufnahme” (recording) above the white line and “Wiedergabe” (playback) below the black line. Evidently, only the start and end points of these two operations are clearly established. These minimal annotations are the only possible forms of writing, as the parts recorded before or during the performance change each time according to the interpreters’ choices. The performers may choose – although within the combinations predetermined by the composer – how to combine the structures written in the score and to be played live with one or two different recorded structures played back on tape. 57 The line, as a one-dimensional graph, thus corresponds to the temporal presence of the electronic sound dimension, and in particular to the operations (recording and playback) to be carried out in combination with the structures to be performed live in front of the audience.

Figure 7 Mauricio Kagel, detail of page 20C from the printed score of Transición II (see Kagel 1963a, 20C). © Mit freundlicher Genehmigung der Universal Edition AG.

Final Remarks

Returning to the initial theoretical assumption, according to which particular forms of writing music within the compositional process obtain an operative quality, it is now possible to point out how the four discussed visual strategies within the development of Transición II can be considered as ‘operative devices’ fulfilling specific functions in the creative process. In particular, it becomes clear how the tone row tables are prepared to arrange the pitches according to serial principle, how rotatable discs are used in aleatoric sections, how a graph on millimetre paper depicts the sound trajectory of a specific section, and how lines coordinate the interplay between recorded and live sound productions.

What makes these forms of writing ‘operative’ is their potential to generate results that enable the composer to advance the compositional project and for the performers to develop their own interpretation. Within the compositional process, the operativity of writing is triggered by precise result-oriented intentions, which may sometimes be modified or questioned during the process of writing or not be realised at all. Fundamentally, though, there is an intentional movement that is realised and developed through visual strategies, which, in turn, allows to attain a higher degree of knowledge.

Although this study is based on a small selection of documents, it demonstrates that Kagel’s imagination of sound had a continuous and productive relationship with written signs and graphical forms, as is also evidenced by his references to a need to be able to precisely write down his own ideas. 58 This relationship with the writing must also be maintained in a certain physical and interactive manner by the performers, both during the unavoidable study phase of the score as well as in the performance. Kagel goes so far as to give indications with regard to the properties of music stands in the introduction to the score. 59 He recommends that “in case of extremely complex pages – e.g., page 26 – each performer should write out a transcription of the version decided upon.” 60 Fundamentally, the performance of Transición II is, in a way, created through the exchange between the writing and the interpreters themselves; in this sense, memorisation for performance would be an entirely unreasonable task.

Following the conviction that the composer must engage in “constant stock-taking of the available ‘writing tools’ so that he can adequately express his ideas”, 61 Kagel omnivorously collects and reworks traditions and trends in musical writing, that is to say, he included and assimilated many different graphic strategies or ‘writing tools’ derived from the trends and traditions with which he came into contact. In this sense, Transición II ’s manuscripts trace his complete immersion within a music-historical context full of new influences to be critically elaborated.

With regard to the question of the validity of musical notation, Kagel points out the composer’s need to explore imagined dimensions through the act of writing itself.

The scale of evaluation for validity or invalidity in the latest forms of musical notation is still subject to the question of the quality of the solution. This question is at once misleading and burdensome when applied to those objects which make no claim to a standard, since they represent in the first instance the tentative exploration of previsioned spheres. 62

The exploratory tension afforded by what is still unknown (and unheard), the openness to repertoires of forms from several origins, and the need to educate the eye not to remain bound to predefined sound concepts are for Kagel the fundamental characteristics of the composer’s attitude. 63 The close study of results of his research to ascertain “for each compositional circumstance, the most suitable form of writing” 64 finally sheds new light on the interdependency between his explorative compositional thinking and the practices of writing music.

References

- Appel, Bernhard R. (2005), “Sechs Thesen zur genetischen Kritik kompositorischer Prozesse”, in: Musiktheorie 20 (2), 112–122.

- Attinello, Paul Gregory (2002), “Imploding the system: Kagel and the deconstruction of modernism”, in: Postmodern music/postmodern thought. Studies in contemporary music and culture, ed. by Judy Lochhead and Joseph Auner, New York: Routledge, 263–285.

- Boehmer, Konrad (1967), Zur Theorie der offenen Form in der neuen Musik, Darmstadt: Tonos.

- Borio, Gianmario / Hermann Danuser (eds.) (1997), Im Zenit der Moderne. Die Internationalen Ferienkurse für Neue Musik Darmstadt 1946–1966, Freiburg i.Br.: Rombach.

- Decroupet, Pascal (1995), “Rätsel der Zahlenquadrate: Funktion und Permutation in der seriellen Musik von Boulez und Stockhausen”, in: Positionen: Beiträge zur Neuen Musik 23, 25–29.

- Dörstel, Wilfried (1993), “‘Knollengewächs’ und ‘Rangierstelle’. Europäische konkrete Kunst und amerikanischer Konkretismus im Atelier Mary Bauermeister”, in: Intermedial kontrovers experimentell. Das Atelier Mary Bauermeister in Köln 1960–62 , ed. by Historisches Archiv der Stadt Köln, Köln: Emons Verlag, 136–149.

- Grésillon, Almuth (2015), “Critique génétique und génétique musicale”, in: Beethovens Werkstatt: genetische Textkritik und digitale Musikedition . https://beethovens-werkstatt.de/prototyp/expertenkolloquium/critique-genetique-und-genetique-musicale/ (23.6.2020).

- Hay, Louis ed. (1979), Essais de critique génétique , Textes et manuscrits, Paris: Flammarion.

- Heile, Björn / Martin Iddon (2009), Mauricio Kagel bei den Internationalen Ferienkursen für Neue Musik in Darmstadt: eine Dokumentation, Hofheim: Wolke.

- Heile, Björn (2006), The music of Mauricio Kagel . Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Kagel, Mauricio (1959), “Ton-Cluster, Anschläge, Übergänge”, in: Die Reihe 5 (Berichte, Analysen) , ed. by Herbert Eimert and Karlheinz Stockhausen, Wien: Universal Edition, 23–37.

- Kagel, Mauricio (1960), “Translation – Rotation”, in: Die Reihe 7 (Form – Raum) , ed. by Herbert Eimert and Karlheinz Stockhausen, Wien: Universal Edition, 31–61.

- Kagel, Mauricio (1962), “Transición I: Elektronische Musik 1958–60. Bemerkungen”, in: Neue Musik: kunst- und gesellschaftskritische Beiträge 5/6, 15–17.

- Kagel, Mauricio (1963a), Transición II für Klavier, Schlagzeug und zwei Tonbänder (1958–59) , London: Universal Edition.

- Kagel, Mauricio (1963b), “On the New Musical Graphics.” Ulm. Zeitschrift der Hochschule für Gestaltung , no. 7, 33–35.

- Kagel, Mauricio (1965), “Komposition – Notation – Interpretation”, in: Notation Neuer Musik (= Darmstädter Beiträge zur Neuen Musik , vol. 9), ed. by Ernst Thomas, Mainz: Schott, 55–63.

- Kagel, Mauricio (1997), “John Cage en Darmstadt 1958”, in: Im Zenit der Moderne , ed. by Gianmario Borio and Hermann Danuser, vol. 3, 484–484. Originally published in Buenos Aires Musical , 16 October 1958.

- Klee, Paul / Jürg Spiller (eds.) (1956), Das bildnerische Denken: Schriften zur Form- und Gestaltungslehre , Basel: Benno Schwabe.

- Klee, Paul (1953), Pedagogical Sketchbook, trans. by Sibyl Moholy-Nagy (1st ed. 1925), New York: F. A. Praeger.

- Krämer, Sybille (2003), “‘Schriftbildlichkeit’ oder: Über eine (fast) vergessene Dimension der Schrift”, in: Bild, Schrift, Zahl , ed. by Sybille Krämer and Horst Bredekamp, München: Fink, 157–176.

- Krämer, Sybille (2005), “‘Operationsraum Schrift’: Über einen Perspektivenwechsel in der Betrachtung der Schrift”, in: Schrift: Kulturtechnik zwischen Auge, Hand und Maschine , ed. by Gernot Grube, Werner Kogge and Sybille Krämer, München: Fink, 23–57.

- Krämer, Sybille (2009), “Operative Bildlichkeit: Von der ‘Grammatologie’ zur ‘Diagrammatologie’? Reflexionen über erkennendes ‘Sehen’”, in: Logik des Bildlichen , ed. by Martina Heßler and Dieter Mersch, Bielefeld: Transcript, 94–122. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839410516-003

- Krämer, Sybille (2014), “13. Schriftbildlichkeit”, in: Bild: Ein interdisziplinäres Handbuch , ed. by Stephan Günzel and Dieter Mersch, Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler, 354–360.

- Krämer, Sybille (2017), “Why notational iconicity is a form of operational iconicity”, in: Dimensions of Iconicity , ed. by Angelika Zirker, Matthias Bauer, Olga Fischer, and Christina Ljungberg, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, 303–321. https://doi.org/10.1075/ill.15.17kra

- Ligeti, György (1960), “Wandlungen der musikalischen Form ”, in: Die Reihe 7 (Form – Raum) , ed. by Herbert Eimert and Karlheinz Stockhausen, Wien: Universal Edition, 5–17.

- Schnebel, Dieter (1970), Mauricio Kagel: Musik Theater Film . Cologne: DuMont.

- Steigerwald, Pia (2011), “An Tasten”: Studien zur Klaviermusik von Mauricio Kagel, Hofheim: Wolke.

- Stockhausen, Karlheinz (2011), “Kommentare zu Transición II ”, in: Pia Steigerwald, “An Tasten”: Studien zur Klaviermusik von Mauricio Kagel , Hofheim: Wolke, 289–307.

- Thomas, Ernst (ed.) (1965), Notation Neuer Musik (= Darmstädter Beiträge zur Neuen Musik , vol. 9), Mainz: Schott.

- Urbanek, Nikolaus (2013), “Was ist eine musikphilologische Frage? ”, in: Historische Musikwissenschaft , ed. by Michele Calella and Nikolaus Urbanek, Stuttgart: Metzler, 147–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-476-05348-0_8

- Zimmermann, Heidy (2008), “Notationen Neuer Musik zwischen Funktionalität und Ästhetik”, in: Notation. Kalkül und Form in den Künsten , ed. by Hubertus von Amelunxen, Dieter Appelt, and Peter Weibel, Berlin: Akademie der Künste, 198–211.